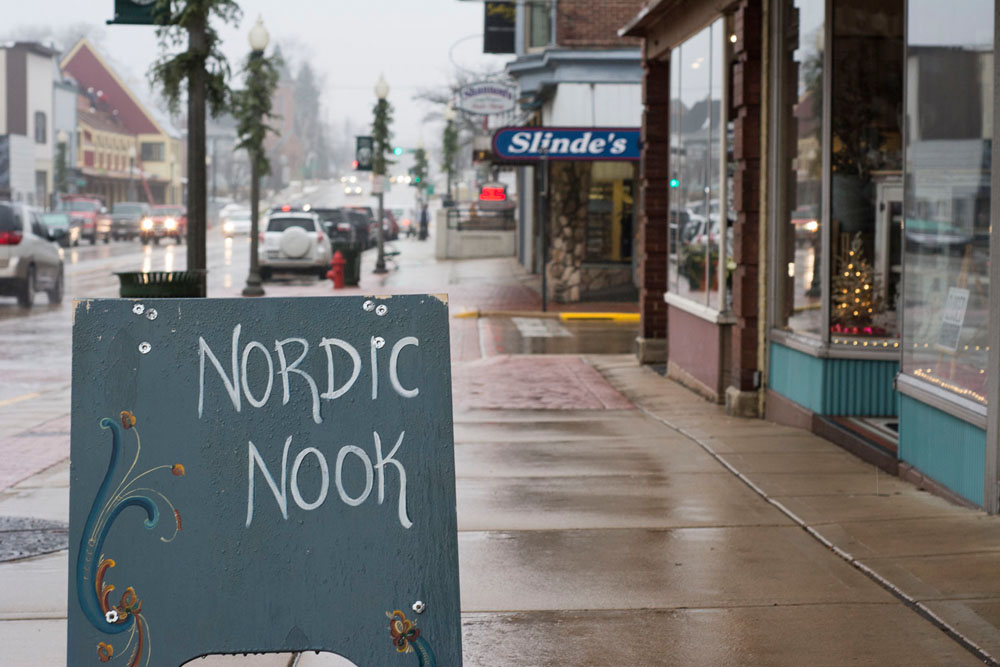

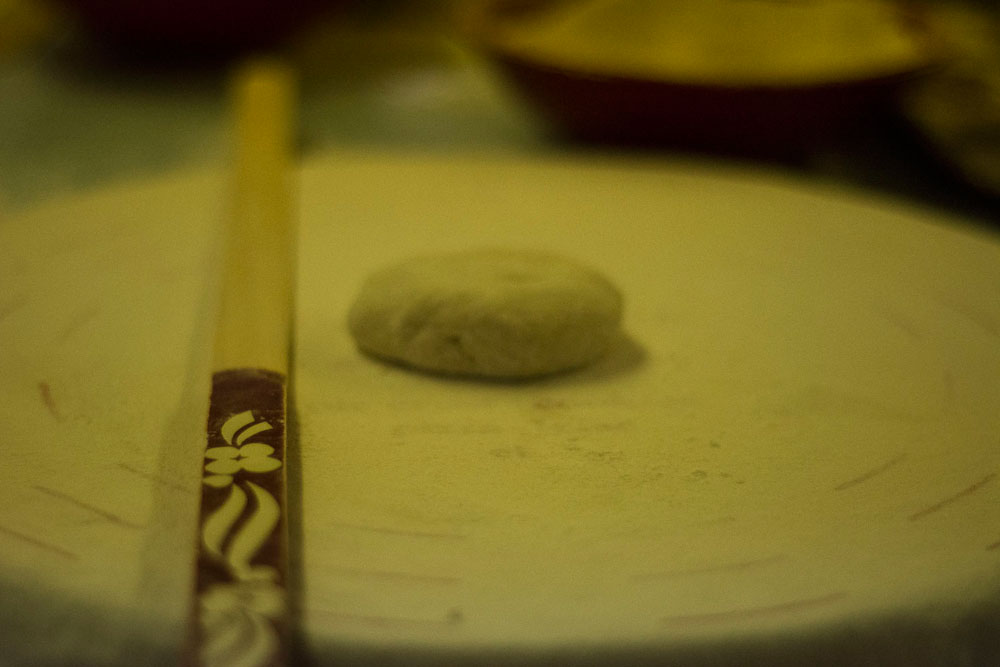

How does one locate a story at the intersection of truth, lies, memory, and imagination? Whatever. . . Never Mind, or Old Torvald Skaalen Died on Saturday is a place-based attempt to play with this question. It is both a piece of short fiction and a documentary photo essay, structured in the style of a children’s book, a form notable for its close and deliberate combination of image and text. I spent a bracing December day taking photographs of the small town of Stoughton (pronounced stoh-tun), Wisconsin. Founded in 1847 and located approximately thirty miles south of Madison, it rapidly grew into a Norwegian immigrant settlement community. Today, the town still places remarkable emphasis on its Norwegian American immigrant history, visible in its iconography, experienced through its cultural celebrations, and understood through its economic development strategy. Along with photographing the built landscape of Stoughton, I spent a day taking interior shots of the local public library and capturing inventory in a Norwegian gift shop on the town’s picturesque main street. That evening, I joined a group of community members from the local Sons of Norway Mandt Lodge as they prepared batches of Norwegian lefse (pronounced lef-sah), a traditional flatbread made of potatoes and flour, rolled paper-thin and cooked on a griddle—in preparation for their children’s Christmas pageant. The following story took shape upon repeated consideration of the photos, using two pubs that sit across the street from one another — the Whatever and the Nevermind — as a departure point. This is the tale of an old curmudgeon named Torvald Skaalen, a man who is simply fed up with being Norwegian.

*with special thanks to UW-Madison Visiting Artists: writer, Brad Zellar, and photographer, Alec Soth; The Nordic Nook in Stoughton; and the generous and spirited crew of lefse-making champions at the Sons of Norway Mandt Lodge, especially Darlene and John Arneson.

which was just as well, because Asmund and Elsa yearned to get back to their regular routine. The day began with their dog, Halldor, fetching The Courier newspaper,

and Elsa sipped her coffee—black and spelled with a “k,” which made it Norwegian coffee, of course.

Asmund flipped open The Courier—torn by Halldor’s maladroit retrieval—and paused on an obituary. “Well,” Asmund sighed to Elsa, “it looks like the gods delivered Old Torvald Skaalen to the North Lights on Saturday.”

as Asmund surveyed the funeral details at First Lutheran church. And though Elsa didn’t want to say anything mean-spirited—it just wasn’t the Norwegian way—she couldn’t stop herself. “Whatever…NEVER MIND TORVALD SKAALEN; I didn’t care for the man,” she confessed.

“Why,” asked Asmund, confused. “Because he was a sour old grouch, and a cynic, and he hated Norwegians!,” screamed Elsa.“But he was a Norwegian,” frowned Asmund.

with the Turkish baker and that Lebanese cab driver, and he spent his days judging us!” Elsa went on. “AND DO YOU KNOW THE THINGS HE SAID?!” “No, tell me,” Asmund implored.

“That he detested his name, everyone’s name—Arnestad and Chistofferdtr. . . Fjaagesund and Lysvold and Staverlokken. . . Froya and Dagne and Markus. ‘ Nothing but a monoculture,’ Torvald groused to his pals, ‘consonants indiscriminately lined up in awkward succession,’ he said.”

Elsa couldn’t stop. “ ‘And Torvald!’ Torvald would say, ‘What kind of a name is Torvald?! Just another Viking ghost in a land where the conquering industry is restructuring. . . brute force displaced. . . ships that moved giants overtaken by algorithms that move money,

Elsa continued, “Then Torvald would preach, ‘Now ‘Ahmed,’ THAT’s a name, and ‘Samaa,’ and ‘Jorge’! . . . names of peace. . . . names of struggle. . .

Having been quiet for a considerable amount of time, Asmund cautiously chimed in, “I think you’re exaggerating about old Torvald, Elsa.” “I most certainly am NOT,” she barked, “and do you know what else?!

Asmund began to understand the Olympic proportions of Elsa’s rant. Still, she persevered, “Torvald said the only thing that he and the trolls saw eye to eye on was that humans carry a stench!”

His minor sympathies with the trolls notwithstanding, he said Norwegians are fools for building monuments to heinous creatures who eat children and then count their gold in mountain kingdoms hidden behind austere, moss-covered doors.”

Elsa pressed on, “Torvald complained that our sense of time was off, that we think in centuries or, at best, days at sea. . . while the rest think in nanoseconds and gigahertz.

Torvald whined that nothing good ever came from a North Wind, even our stories. . . said Knut Hamsun was a Nazi and all three of the Billy Goats Gruff unapologetically fat and greedy.

Finally, Elsa fell silent. Asmund moved over and held her tightly, hoping to extinguish her ire. “You’re being ungenerous toward Old Torvald, my love.”

Asmund pleaded, “Let’s revisit the trolls! Torvald may very well have hated them, but he got them all wrong. Good Norwegians know that the most famous and powerful trolls have multiple heads. . . 5, 10, 50! You and me? We have them, too. But poor Torvald, he had only one. . .

Asmund looked at his sweet, “Torvald is at peace. So, be kind, dear Elsa. And I agree with you. . . Whatever. . . never mind Torvald Skaalen.” THE END